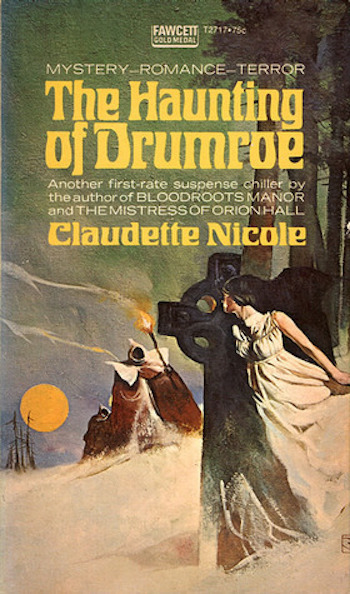

The Haunting of Drumroe

Claudette Nicolle | Fawcett Gold Medal | 141 pages | 1971

Eileen Donegan returns to Ireland and her ancestral family home after receiving a cryptic letter of help from her aunt Agnes, Lady Donegon of Drumroe. Driving to the remote estate, Eileen is nearly killed by a tree falling across the road, sending her rental car plunging into a lake. Finally arriving at the great house, she is alarmed to discover that her aunt has gone missing, and that none of the household staff can explain her absence.

A familiar gothic thriller template is further established with the introduction of two competing love interests for Eileen, the dark-haired solicitor Rory Muldoon and the gray-eyed local historian Colin Riorden. A bit of unnecessary backstory relating to Eileen’s philandering ex-husband lays the groundwork for her shifting affections between the two men, which is expressed mostly through some feverish hand holding and a few chaste kisses.

Claudette Nicolle is a pseudonym for John Messman, who wrote a number of these genre staples, almost universally featuring covers depicting women in nightgowns running away from castles. Hints of this underlying male authorship abound by the fascination with Eileen’s sleeping in the nude, and the repeated references to her firm and ample breasts.

Although there are no actual hauntings in The Haunting of Drumroe, supernatural elements emerge through Eileen’s psychic abilities. Reportedly descended from an infamous local witch, Eileen has received psychic impressions of family tragedies at various periods throughout her life, some at great distance. Now, her psychic impressions tell her that aunt Agnes is dead, although the details are maddeningly scarce.

Beyond simply “knowing” that her aunt is dead, Eileen’s psychic talents are mostly underutilized and not particularly relevant in solving the mystery. Eileen is even less gifted as a traditional detective, since she seems bluntly oblivious to the fairly overt clues leading to the person responsible for her aunt’s disappearance, the attempts on her own life, and a laundry list of other mysterious deaths in the family.

The Irish setting is modestly rendered, but appealing: the small villages, the rolling hills, the chilly lough, the lonely cemetery, and—of course—the weird pagan rituals in the woods at night. The political violence in Northern Ireland is introduced as a possible explanation for an attack on Eileen, but it does feel slightly out of place in an otherwise standard genre work that could have easily been set in the nineteenth century.

A perfectly serviceable, if altogether unmemorable, gothic thriller.